Freddie Mercury's modest London home gets blue plaque

Neighbours in suburb of Feltham remember noisy neighbour who became flamboyant Queen star

Brian May and Kashmira Cooke, Freddie Mercury’s sister, at the unveiling.

Brian May and Kashmira Cooke, Freddie Mercury’s sister, at the unveiling.

Neighbours in suburb of Feltham remember noisy neighbour who became flamboyant Queen star

Brian May and Kashmira Cooke, Freddie Mercury’s sister, at the unveiling.

Brian May and Kashmira Cooke, Freddie Mercury’s sister, at the unveiling.

Photograph: Stuart C Wilson/Getty ImagesMaev Kennedy Thursday 1 September 2016 15.15

The present occupier of Freddie Mercury’s bedroom in the London suburb of Feltham, nine-year-old Daria Mihailuka, was playing it cool amid the hordes of media camped on her narrow street of brick and pebble-dash terraced houses. “I’m not like his greatest fan,” she said of the late Queen singer. “I’m more into modern music – I like Justin Bieber.”

But Daria said Mercury’s trajectory, from the springboard of the small suburban bedroom to one of the biggest pop stars in the world, was an inspiration. “I want to be a singer-actor-dancer, and I am a good achiever – my vocal skills can get better – and he shows me that you can start out just right here and become a huge star.”

The house in Feltham. Photograph: Nils Jorgensen/Rex/Shutterstock

The house’s owner, family friend Ray Edwards, shook his head in amazement at the coterie assembled on his small front garden: Mercury’s sister Kashmira Cooke; the new culture secretary, Karen Bradley; former arts council chair and English Heritage blue plaque panel member Sir Peter Bazalgette; and, towering over them and the garden wall lined with cameras, Queen guitarist Brian May and his silver mop of curls.

Fortunately Edwards is a serious fan. When Bohemian Rhapsody is blasting out too loud, Daria shouts down from her room: “Turn it down Ray!” He thought the estate agent was winding him up when he was told the Bulsara family – Freddie’s birth name was Farrokh Bulsara – had previously owned the house.

Although a paradise for plane spotters due to its proximity to Heathrow, even Feltham’s most loyal residents would hardly describe the west London suburb – where Mercury once had a holiday job washing dishes – as glamorous. On Thursday however, there was nearly as much excitement on Gladstone Avenue as when Mercury used to arrive in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce to visit his mother.

Mercury, the embodiment of flamboyance and effervescence, died in 1991 of an Aids-related lung condition, aged 45. Outside the Feltham home, Mercury’s immaculately dressed cousin Pouras Dastur remembered the neighbourhood’s reaction to the teenaged Mercury’s homemade, hand-embroidered velvet flared trousers: “Heads turned.” His sister remembers competing for the only bathroom with a brother whose hair was high maintenance even then.

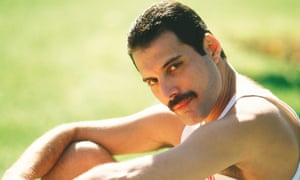

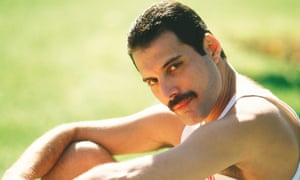

Freddie Mercury. Photograph: Courtesy of Universal

Many neighbours well remember the family, and their occasionally noisy son. Carole and Derick Burgess bought their house in 1964, a month before the Bulsaras – still family friends – moved in two doors up, fleeing the revolution that had gripped their home island of Zanzibar.

On summer evenings they remember Mercury practising guitar in the back garden, or in his room with the windows wide open. Burgess is more of a modern jazz man, and remembers snapping to his wife: “Does he only know one chord? When is that boy going to learn to play that guitar?”

May also remembers the small back bedroom. He was another local boy, at one point living only a few hundred yards away, when he was introduced to the Ealing Tech art student through the singer of his first band, Smile. Mercury insisted they listen to a Jimi Hendrix track on his Dansette record player – the posh model with the autochanger. “Yeah, Jimi Hendrix, great,” May said, but Mercury forced them to listen to it again and again, bouncing around the place in excitement, analysing the sound and the production technique bar by bar. “That’s what we’re going to do. We’re gonna be a group,” Mercury assured him. “I was thinking, well … can you even sing?” May recalled.

As it turned out he could, with one of the most spectacular vocal ranges in pop music. “I won’t be a rock star, I will be a legend,” May remembered him saying. And that turned out to be true too.

Bazalgette, as a member of the blue plaques panel, pushed hard for the honour for the modest house and the immodest man, but he was pushing an open door: many of the others agreed that Queen’s music was “the soundtrack of our lives”.

The culture secretary nodded in agreement: the first number Bradley can remember watching on Top of the Pops was Bohemian Rhapsody, and the jukebox in her parents’ pub, the appropriately named Queen’s Head in Buxton, took more money from it than from all the other records together.

“This is a very happy occasion,” May said, “with a tinge of sadness – because he should be here.”

The present occupier of Freddie Mercury’s bedroom in the London suburb of Feltham, nine-year-old Daria Mihailuka, was playing it cool amid the hordes of media camped on her narrow street of brick and pebble-dash terraced houses. “I’m not like his greatest fan,” she said of the late Queen singer. “I’m more into modern music – I like Justin Bieber.”

But Daria said Mercury’s trajectory, from the springboard of the small suburban bedroom to one of the biggest pop stars in the world, was an inspiration. “I want to be a singer-actor-dancer, and I am a good achiever – my vocal skills can get better – and he shows me that you can start out just right here and become a huge star.”

The house in Feltham. Photograph: Nils Jorgensen/Rex/Shutterstock

The house’s owner, family friend Ray Edwards, shook his head in amazement at the coterie assembled on his small front garden: Mercury’s sister Kashmira Cooke; the new culture secretary, Karen Bradley; former arts council chair and English Heritage blue plaque panel member Sir Peter Bazalgette; and, towering over them and the garden wall lined with cameras, Queen guitarist Brian May and his silver mop of curls.

Fortunately Edwards is a serious fan. When Bohemian Rhapsody is blasting out too loud, Daria shouts down from her room: “Turn it down Ray!” He thought the estate agent was winding him up when he was told the Bulsara family – Freddie’s birth name was Farrokh Bulsara – had previously owned the house.

Although a paradise for plane spotters due to its proximity to Heathrow, even Feltham’s most loyal residents would hardly describe the west London suburb – where Mercury once had a holiday job washing dishes – as glamorous. On Thursday however, there was nearly as much excitement on Gladstone Avenue as when Mercury used to arrive in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce to visit his mother.

Mercury, the embodiment of flamboyance and effervescence, died in 1991 of an Aids-related lung condition, aged 45. Outside the Feltham home, Mercury’s immaculately dressed cousin Pouras Dastur remembered the neighbourhood’s reaction to the teenaged Mercury’s homemade, hand-embroidered velvet flared trousers: “Heads turned.” His sister remembers competing for the only bathroom with a brother whose hair was high maintenance even then.

Freddie Mercury. Photograph: Courtesy of Universal

Many neighbours well remember the family, and their occasionally noisy son. Carole and Derick Burgess bought their house in 1964, a month before the Bulsaras – still family friends – moved in two doors up, fleeing the revolution that had gripped their home island of Zanzibar.

On summer evenings they remember Mercury practising guitar in the back garden, or in his room with the windows wide open. Burgess is more of a modern jazz man, and remembers snapping to his wife: “Does he only know one chord? When is that boy going to learn to play that guitar?”

May also remembers the small back bedroom. He was another local boy, at one point living only a few hundred yards away, when he was introduced to the Ealing Tech art student through the singer of his first band, Smile. Mercury insisted they listen to a Jimi Hendrix track on his Dansette record player – the posh model with the autochanger. “Yeah, Jimi Hendrix, great,” May said, but Mercury forced them to listen to it again and again, bouncing around the place in excitement, analysing the sound and the production technique bar by bar. “That’s what we’re going to do. We’re gonna be a group,” Mercury assured him. “I was thinking, well … can you even sing?” May recalled.

As it turned out he could, with one of the most spectacular vocal ranges in pop music. “I won’t be a rock star, I will be a legend,” May remembered him saying. And that turned out to be true too.

Bazalgette, as a member of the blue plaques panel, pushed hard for the honour for the modest house and the immodest man, but he was pushing an open door: many of the others agreed that Queen’s music was “the soundtrack of our lives”.

The culture secretary nodded in agreement: the first number Bradley can remember watching on Top of the Pops was Bohemian Rhapsody, and the jukebox in her parents’ pub, the appropriately named Queen’s Head in Buxton, took more money from it than from all the other records together.

“This is a very happy occasion,” May said, “with a tinge of sadness – because he should be here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment