A Queen Mystery: The Legend of The Deacy Amp

Source: Adam Fabio May 8, 2017 http://hackaday.com/2017/05/08/a-queen-mystery-the-legend-of-the-deacy-amp/#comment-3560168

It sounds like a scene from a movie. A dark night in London, 1972. A young man walks alone, heading home after a long night of practicing with his band. His heavy Fender bass slung over his back, he’s weary but excited about the future. As he passes a skip (dumpster for the Americans out there), a splash of color catches his attention. Wires – not building power wires, but thinner gauge electronics connection wire. A tinkerer studying for his Electrical Engineering degree, the man had to investigate. What he found would become rock and roll history, and the seed of mystery stretching over 40 years.

The man was John Deacon, and he had recently signed on as bassist for a band named Queen. Reaching into the skip, he found the wires attached to a circuit board. The circuit looked to be an amplifier. Probably from a transistor radio or a tape player. Queen hadn’t made it big yet, so all the members were struggling to get by in London.

Deacon took the board back home and examined it closer. It looked like it would make a good practice amplifier for his guitar. He fit the amp inside an old bookshelf speaker, added a ¼ “ jack for input, and closed up the case. A volume control potentiometer dangled out the back of the case. Power came from a 9-volt battery outside the amp case. No, not a tiny transistor battery; this was a rather beefy PP-9 pack, commonly used in radios back then. The amp sounded best cranked all the way up, so eventually, even the volume control was removed. John liked the knobless simplicity – just plug in the guitar and play. No controls to fiddle with.

And just like that, The Deacy amp was born.

The Sound

Source: Adam Fabio May 8, 2017 http://hackaday.com/2017/05/08/a-queen-mystery-the-legend-of-the-deacy-amp/#comment-3560168

It sounds like a scene from a movie. A dark night in London, 1972. A young man walks alone, heading home after a long night of practicing with his band. His heavy Fender bass slung over his back, he’s weary but excited about the future. As he passes a skip (dumpster for the Americans out there), a splash of color catches his attention. Wires – not building power wires, but thinner gauge electronics connection wire. A tinkerer studying for his Electrical Engineering degree, the man had to investigate. What he found would become rock and roll history, and the seed of mystery stretching over 40 years.

The man was John Deacon, and he had recently signed on as bassist for a band named Queen. Reaching into the skip, he found the wires attached to a circuit board. The circuit looked to be an amplifier. Probably from a transistor radio or a tape player. Queen hadn’t made it big yet, so all the members were struggling to get by in London.

Deacon took the board back home and examined it closer. It looked like it would make a good practice amplifier for his guitar. He fit the amp inside an old bookshelf speaker, added a ¼ “ jack for input, and closed up the case. A volume control potentiometer dangled out the back of the case. Power came from a 9-volt battery outside the amp case. No, not a tiny transistor battery; this was a rather beefy PP-9 pack, commonly used in radios back then. The amp sounded best cranked all the way up, so eventually, even the volume control was removed. John liked the knobless simplicity – just plug in the guitar and play. No controls to fiddle with.

And just like that, The Deacy amp was born.

The Sound

Now guitarists love the term “tone”. It’s used to describe the overall sound of the guitar, amplifier, and any effects devices in between. Words like “mellow” and “crunchy” come into play. It can be hard for a non-guitarist to keep up. John’s amp had a nice warm tone, slightly distorted – yet pleasant to the ear. He used it for awhile, then brought it along to a practice session with his Queen bandmates.

Guitarist Brian May took an interest in the amp. Now Brian is a hacker in his own right. His guitar, the Red Special, was built as a father/son project when Brian was a teen. The Red Special deserves an article all its own, so keep your eyes peeled for that one. Brian often played through a treble booster. This is a single transistor circuit acting as a 30 db preamp. It guarantees any amplifier plugged in will have its input stage driven to distortion.

Plugging this setup into the Deacy amp changed its sound even more. The overdriven amp sounded different from anything they had heard before. Not quite the warm sound of an overdriven tube amplifier, but much smoother than the clipping sound that came from distorted transistor amps of the time. It also had a sustain to it. The Red Special suddenly sounded like a violin, a cello, or even the human voice. Brian loved the sound and kept experimenting with the amp.

Queen’s sound guys loved the amp as well. It was very consistent, which made it suitable for layering tracks in a recording studio. Guitars are typically recorded by connecting them to an amplifier and then pointing a microphone at the amp’s speaker cabinet. Exactly how to place the microphone and amplifier, as well as the settings of each is as much art an art as it is a science.

Plugging this setup into the Deacy amp changed its sound even more. The overdriven amp sounded different from anything they had heard before. Not quite the warm sound of an overdriven tube amplifier, but much smoother than the clipping sound that came from distorted transistor amps of the time. It also had a sustain to it. The Red Special suddenly sounded like a violin, a cello, or even the human voice. Brian loved the sound and kept experimenting with the amp.

Queen’s sound guys loved the amp as well. It was very consistent, which made it suitable for layering tracks in a recording studio. Guitars are typically recorded by connecting them to an amplifier and then pointing a microphone at the amp’s speaker cabinet. Exactly how to place the microphone and amplifier, as well as the settings of each is as much art an art as it is a science.

The dusty Deacy Amp hard at work in 1998. Image Source Glen Fryer

Brian quickly adopted the amp, and it became an integral part of Queen’s early sound. You can hear it in classics such as God Save The Queen, Killer Queen, and the more recent A Winter’s Tale. In my humble opinion, the most interesting use of the Deacy amp would be Good Company, from Queen’s album A Night At the Opera. Brian layered track after track with the Deacy. In the end, he reproduced the sound of an entire brass band, just using his guitar.

And that’s how things stayed – Brian used The Deacy in many recording sessions from the 1970’s all the way through the 90’s. It never failed or needed adjustment. In fact, the amp was never opened after John Deacon built it. That all changed in 1998, While recording “Another World” Greg Fryer asked Brian about building a replica for the now aging Deacy. May agreed, and work soon started on studying the original.

There is a certain level of stress an archaeologist must feel when peeling back layers of dirt at a dig site. Greg Fryer and Pete Malandrone must have felt the same way when first opening the Deacy. The pair had no idea what they would find inside this decades-old hack. There was a real chance they could mess this up, and a working piece of rock history.

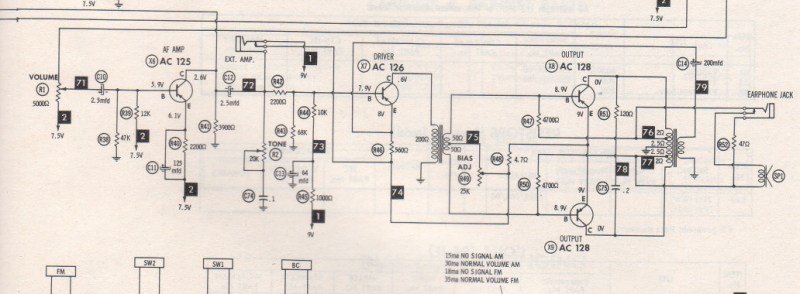

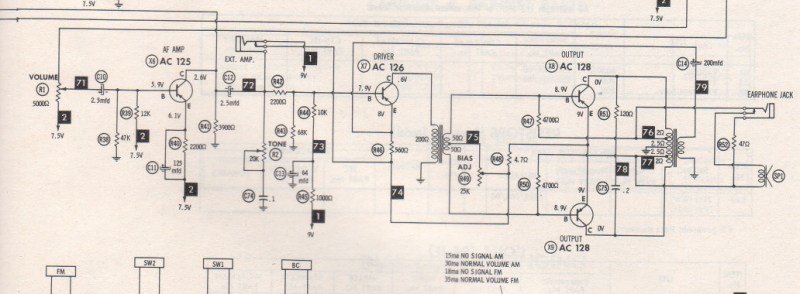

Carefully removing the back, the two found a single circuit board. It was a four-transistor circuit. The power section was a class B amplifier in push-pull configuration. The power transistors were AC128, germanium devices. Both input and output were transformer coupled, with the power transistors mounted above the two multi-tapped transformer cores. It was a bit odd, both electronically and physically, though some parts of the circuit seem to have been taken directly from the Mullard transistor manual.

Brian quickly adopted the amp, and it became an integral part of Queen’s early sound. You can hear it in classics such as God Save The Queen, Killer Queen, and the more recent A Winter’s Tale. In my humble opinion, the most interesting use of the Deacy amp would be Good Company, from Queen’s album A Night At the Opera. Brian layered track after track with the Deacy. In the end, he reproduced the sound of an entire brass band, just using his guitar.

And that’s how things stayed – Brian used The Deacy in many recording sessions from the 1970’s all the way through the 90’s. It never failed or needed adjustment. In fact, the amp was never opened after John Deacon built it. That all changed in 1998, While recording “Another World” Greg Fryer asked Brian about building a replica for the now aging Deacy. May agreed, and work soon started on studying the original.

There is a certain level of stress an archaeologist must feel when peeling back layers of dirt at a dig site. Greg Fryer and Pete Malandrone must have felt the same way when first opening the Deacy. The pair had no idea what they would find inside this decades-old hack. There was a real chance they could mess this up, and a working piece of rock history.

Carefully removing the back, the two found a single circuit board. It was a four-transistor circuit. The power section was a class B amplifier in push-pull configuration. The power transistors were AC128, germanium devices. Both input and output were transformer coupled, with the power transistors mounted above the two multi-tapped transformer cores. It was a bit odd, both electronically and physically, though some parts of the circuit seem to have been taken directly from the Mullard transistor manual.

Cloning an Original

The board was definitely from a low-cost mass-produced piece of consumer electronics. Replicating the basic design would be easy. The hard part would be replicating the transformers. The two transformers were cheaply made and had multiple taps. One could measure the resistance of each tap, but short of unwinding them, it was impossible to know exactly what material the core laminations were, or exactly how many winds there were.

The pair closed the amp up and began designing the replicas. The first try had a similar sound to the Deacy, but wasn’t quite there. Greg continued to refine the design in his spare time. Each iteration getting closer to the Deacy’s sound. By 2003, replicating the amp had become a mission for Greg. He enlisted Nigel Knight to help with the effort. The hope wasn’t just to provide a few amps to Brian but to create replicas which could be purchased. There are thousands of Queen fans out trying to replicate the sound of Brian’s guitar setup. This would be as close as they could get.

In 2008, Brian gave the OK to completely tear down the amp, and determine what exactly was going on. The transistors were individually tested. The transformers were examined and tested by transformer manufacturers who came on board to help. Loops of wire were wrapped around the transformers, creating yet another secondary coil. Injecting and signals on the unknown primaries and reading the output on the known secondaries helped determine the transformer’s performance.

Many parts were found to be wildly out of spec. The AC128’s were both at the far opposite ends of what the datasheets called nominal. In a push-pull amplifier, you would want a matched pair of transistors. This pair was about as far from matched as one could get. The result was that for a sinusoid waveform input, the lower peaks of the waveform would begin clipping long before the upper peaks. This was one of the keys to the Deacy’s sound.

The result of Greg and Nigel’s work was the Knight Audio Technologies Deacy Replica. This wasn’t a cheap unit, pricing at well over 1,000 pounds sterling. It still sold well and satisfied just about everyone, including Brian May himself.

The Origin Mystery, Solved

The mystery still remained – where did the amplifier come from? Nigel postulated that it was originally part of a baby monitor or intercom of some sort, as it was a stand alone amplifier. Usually a radio or tape player would have placed all the parts on one circuit board. Both Greg and Nigel posted photos of the Deacy internals in the early 2000s. This brought the greater Internet on board. Surely the Internet would be able to find the origins of a common circuit board like this.

The mystery still remained – where did the amplifier come from? Nigel postulated that it was originally part of a baby monitor or intercom of some sort, as it was a stand alone amplifier. Usually a radio or tape player would have placed all the parts on one circuit board. Both Greg and Nigel posted photos of the Deacy internals in the early 2000s. This brought the greater Internet on board. Surely the Internet would be able to find the origins of a common circuit board like this.

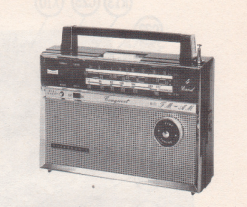

Unfortunately, the answer was no. The years went by, and curious searchers, including this article’s author, found nothing. That is, until January 2013. [Mitch, aka PBPP] on the antique radio forum dropped a bomb of a post. He had found the origin of the Deacy amp board. It was the amplifier section of a transistor radio after all, specifically the Supersonic PR80. He took it a step further and found documentation on the beast, in SAMS Photofact Transistor Radio Series TSM-60, published October 1965.

Supersonic was a company which built consumer electronics in Africa. They manufactured in Rhodesia and South Africa during different periods. Still, this particular model of radio is relatively rare to find. So far, only [Manuel Angelini] has come forward with photographic proof of his own PR80 amp board.

So, while the mystery of the Deacy amplifier origin story was solved, the actual components were just as hard as ever to find. Germanium transistors are becoming quite rare. Soon, the only way to get that Deacy amp yourself will be to fire up some DSP software and simulate it.

Source: Adam Fabio May 8, 2017 http://hackaday.com/2017/05/08/a-queen-mystery-the-legend-of-the-deacy-amp/#comment-3560168

So, while the mystery of the Deacy amplifier origin story was solved, the actual components were just as hard as ever to find. Germanium transistors are becoming quite rare. Soon, the only way to get that Deacy amp yourself will be to fire up some DSP software and simulate it.

Source: Adam Fabio May 8, 2017 http://hackaday.com/2017/05/08/a-queen-mystery-the-legend-of-the-deacy-amp/#comment-3560168

No comments:

Post a Comment